King's College London

The Idea of Lebanon

Rights, Violent Caesuras, and Sequels of Injury

The present in Lebanon retains the imprint of a past which is not yet past, but rather one which is lived, reproduced, and recalibrated on a daily basis. Authored and curated by Madonna Kalousian, this section of the exhibition captures the ramifications of this pervasive embeddedness of multiple layers of meaning from the past and the present as these manifest in modern-day Lebanon. It paints a picture in which the administrative, juridical, geographical, and demographic contours of what becomes Lebanon, particularly as undefined and redefined by colonial rule, continue today to plunge the country into a succession of episodes of harm, injury, and injustice.

It does so by building on an understanding of the idea of Lebanon at various stages of its history, from the late Ottoman times and the French Mandate to the post-independence era and the present-day regional escalation of violence inflicting further harm onto the post-civil war reality of a population whose injuries are not only yet to heal, but also continue to multiply.

قَانُون الجَزاء

Ottoman Criminal Law

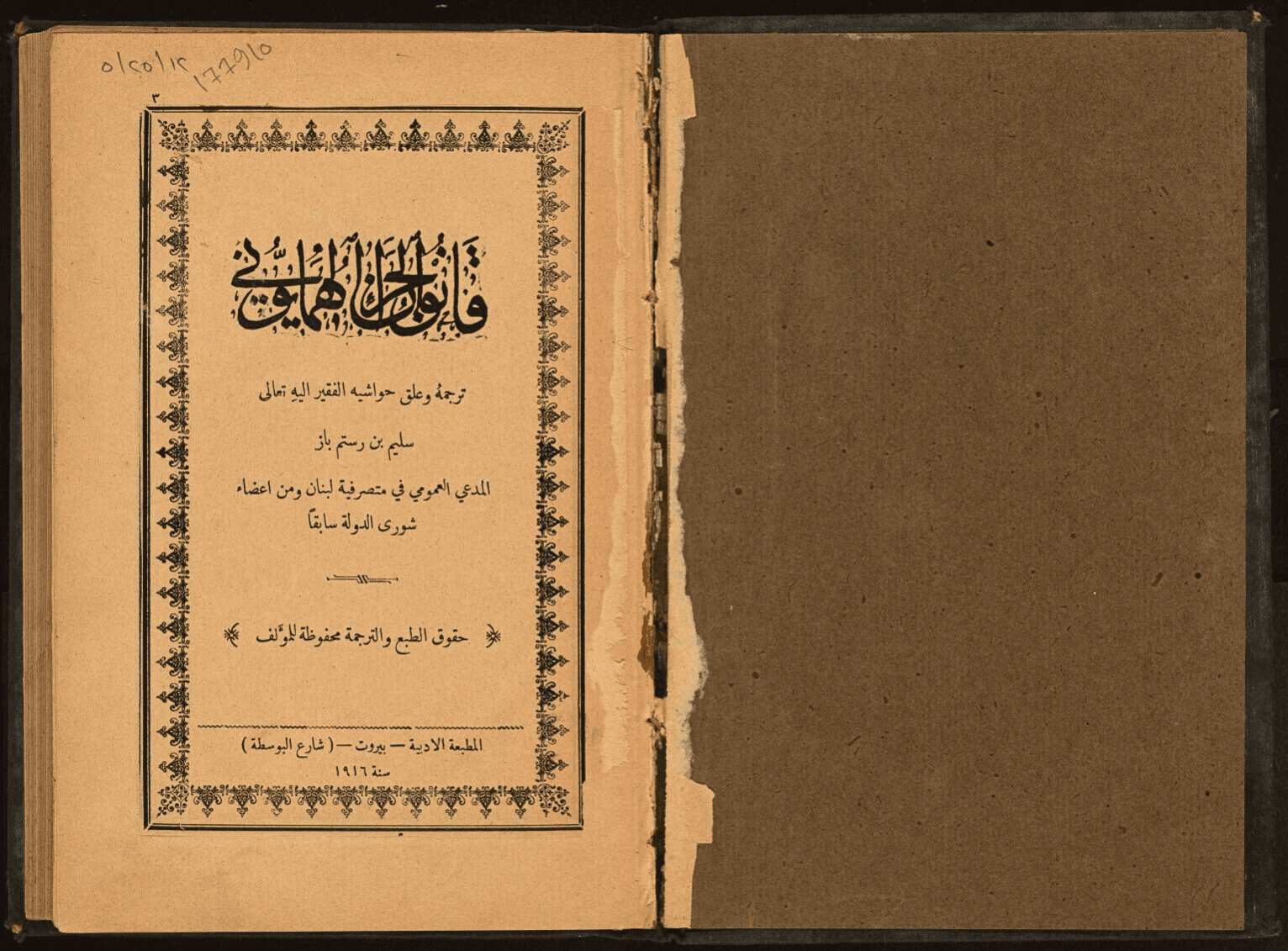

Lebanese historian, supreme judge, and member of majlis al-shūra (Lebanese state council) under Ottoman rule Salim Rustum Baz (1858-1920) translated Ottoman criminal law, including some of the most recent amendments it introduced to the millet system, into Arabic. Drawing on rulings and articles he found in magazines and newspapers, Baz published his compilations of and notes on Ottoman criminal law in this edition of qānūn al-jazāʾ al-humayyūni (Ottoman Criminal Law). This was published by al-maṭbaʿa al-adabiyya in Beirut in 1916 and was intended to be used by judges, lawyers, and students.

National Library of Qatar

| 12945 | رقم الاستدعاء |

| قانون الجزاء الهمايوني | العنوان |

| F-1-1 - F-1-186 | الصفحات |

| مكتبة قطرالوطنية | المؤلف |

| نطاق عام | شروط الاستخدام |

Rights, Millets, and the Governance of Belonging

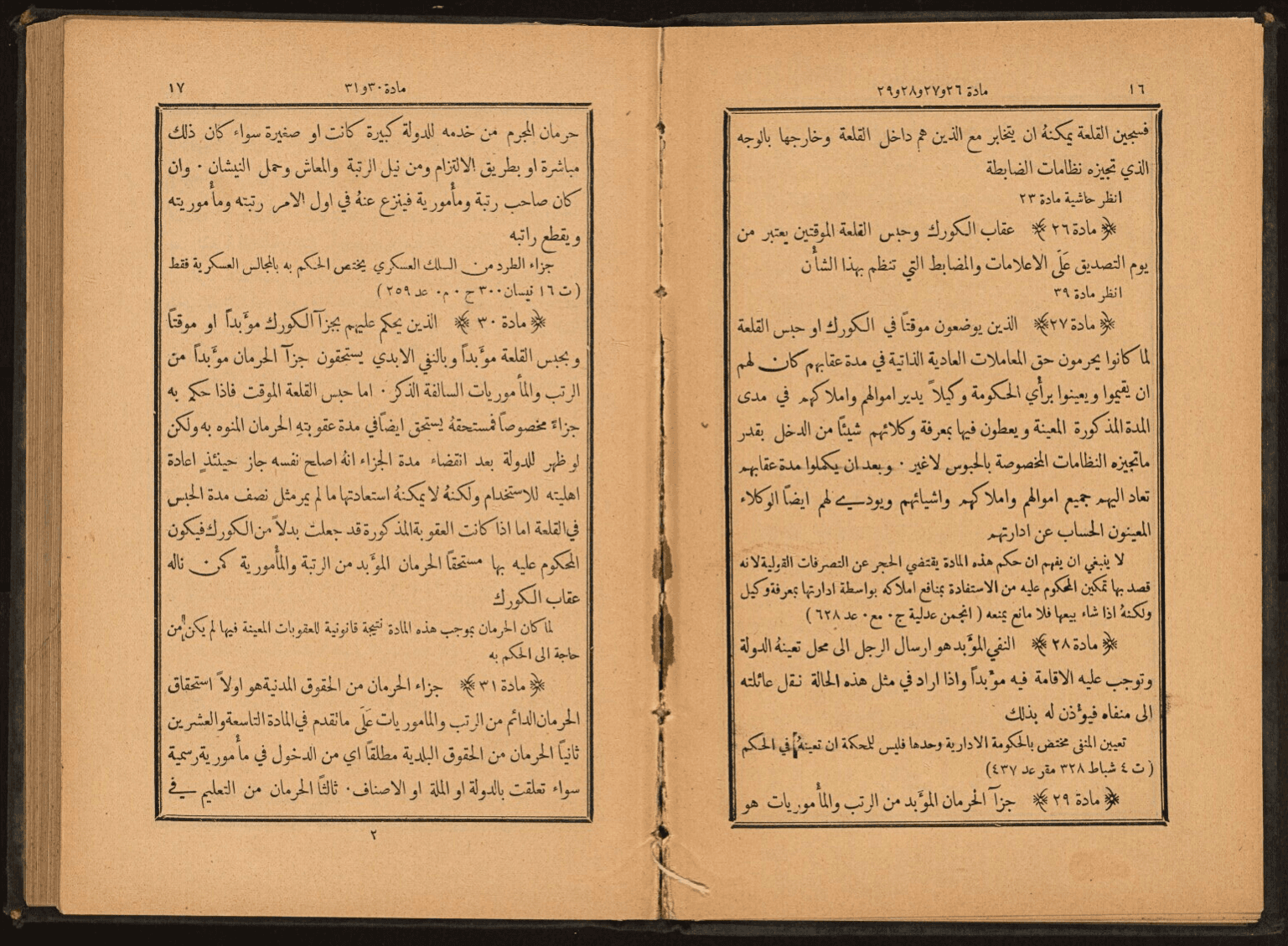

The Ottomans introduced a set of regulations governing the rights a subject or a citizen is granted within a community. Some of these rights, as mentioned by Baz in Article 31 for instance, include al-ḥuqūq al-madaniyya (civil rights) and al-ḥuqūq al-baladiyya (administrative rights), governed by autonomous administrative councils and a range of sect-based courts operating within a millet system. As a form of governance, the millet system imposed a number of measures regulating multiple aspects of the life of non-Muslim communities, “from what ordinary Christians and Jews could wear, to the places of worship they could build, to the jizya (poll tax) they had to pay […] in return for social, fiscal, and political subordination” (Makdissi 2019, 19).

National Library of Qatar

| 12945 | رقم الاستدعاء |

| قانون الجزاء الهمايوني | العنوان |

| F-1-1 - F-1-186 | الصفحات |

| مكتبة قطرالوطنية | المؤلف |

| نطاق عام | شروط الاستخدام |

سالنامۀ دَوْلَتِ عَلِیّهٔ عُثمَانِیّه

Yearbooks of the Sublime Ottoman State

Between 1847 and 1918, the Ottoman state published state yearbooks, known as سالنامۀ دَوْلَتِ عَلِیّهٔ عُثمَانِیّه, intended to provide the public with a comprehensive range of information in relation to a number of issues, such as local and foreign state affairs, notable dates in the calendar, records of appointed state, military, council, and court officials, and any other relevant announcements on fees, taxes, economic affairs, and public health.

The yearbooks also provided an annual overview of Ottoman structures of governance within what is referred to in the yearbooks as ولايات عثمانية (Ottoman provinces) and الوية مستقلة (autonomous provinces), each with their own sets of Ottoman and autonomous administrative rights.