Colombia

Extractivism and the Governance of Indigenous Peoples in Colombia: Between Injury and Resistance

Since the violent imposition of Spanish colonial rule in the 1500s, indigenous peoples in Colombia have been subjected to multiple injuries produced by the extraction of natural resources and external forms of governance. This exhibition, authored and curated by Dr Jennifer Bates, uses visual and textual material including maps, photographs and documents to trace extractivism and the governance of indigenous peoples from the colonial era, to Colombia’s independence after 1819, through to the present day. It examines the continuities in dispossession and subordination of indigenous communities produced by the extraction of gold during colonial rule, and coal extraction since the 1970s. In parallel, the material explores changing forms of governance as they relate to and constitute indigenous rights, and the emergence of indigenous resistance centred on the reclamation of land. While revealing the significant strides made through indigenous political struggles for land, the exhibition also highlights the fundamental, historically rooted tension between indigenous land rights and the logics of extraction that lead to dispossession and damage to their lands.

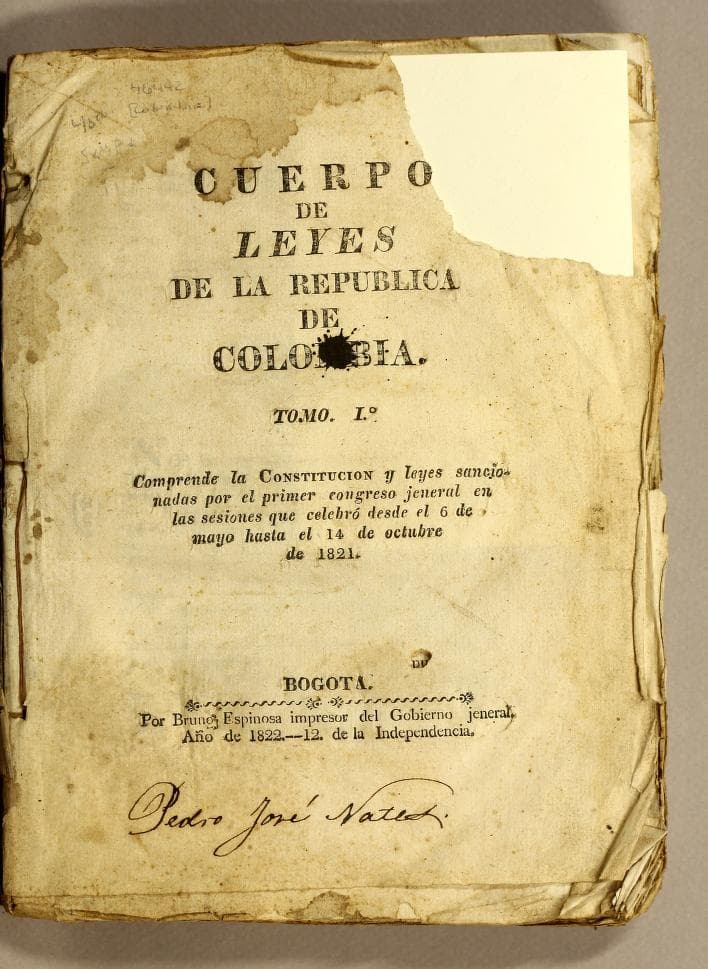

The Dissolution of Resguardos Post-independence

The decrease in resguardos gained further momentum after Colombia’s independence from Spain in 1819. Post-independence political elites saw resguardos and the payment of tribute as a colonial inheritance which prevented indigenous people from assimilating into the nation. Influenced by economic liberalism and its emphasis on private property rights, they moved to convert communal resguardo lands into private property to be bought and sold. Pictured here is Colombia’s 1821 constitution, which includes a law that establishes the equality of indigenous peoples before the law, abolishes the payment of tribute and distributes resguardo land as private property.

(Re)constituting Indigenous Rights in the 1886 Constitution

The , which remained in effect until 1991, contains a homogenous view of the nation as centralised, Catholic and Spanish speaking, and makes no reference to indigenous peoples, who were exempted from the legislation of the republic in Law 89 of 1890. Law 89 reaffirmed the role of the Catholic Church in governing indigenous peoples’ lives and slowed the dissolution of resguardos (reserves) by defining them as inalienable. The law was introduced by the Conservative party with the aim of slowing tribute payments, and only pausing the dissolution of resguardos until indigenous peoples had been ‘reduced to civilized life.’

Governance Through Assimilation

Under the tutelage of the Church, indigenous peoples were expected to leave behind their culture and customs and assimilate into wider society. The book below, Presidential Excursions: Notes from a Travel Diary (1909), reflects political elites’ attitudes towards indigenous people. At the same time that indigenous people are othered, they are praised for speaking Spanish, converting to Catholicism and expressing affection for the president. The book was written by P. A. Pedraza, chief commander of the National Gendarmerie, to document the travels of President Rafael Reyes (1904-9) to areas on Colombia’s Caribbean coast.

Click on the arrow to view excerpts from the book and click on the icon to see English translations of the text.

Pastoral Power

These photos come from an article on the Arhuaco indigenous group, written by the Franciscan missionary Padre Jose de Vinalesa and published in the Journal of the National Ethnological Institute in 1952. Highlighting the intersection between evangelising missions and ethnographic knowledge of indigenous communities, the article contains in-depth details on Arhuaco customs, spiritual beliefs and language. At the same time, they are described in essentialist terms:

The Arhuaco indian carries with him the defects common to almost all indians; who are generally selfish, suspicious, without aspirations; inclined to laziness and drunkenness. However: if we carefully study the character of the Arhuaco race, we will be able to appreciate in its individuals good qualities and even a certain innate disposition for good.

Click on each photograph to see an English translation.