1976

Colombian state company Carbocol and Intercor, a subsidiary of Exxon, sign a 50-50 contract to develop the mine.

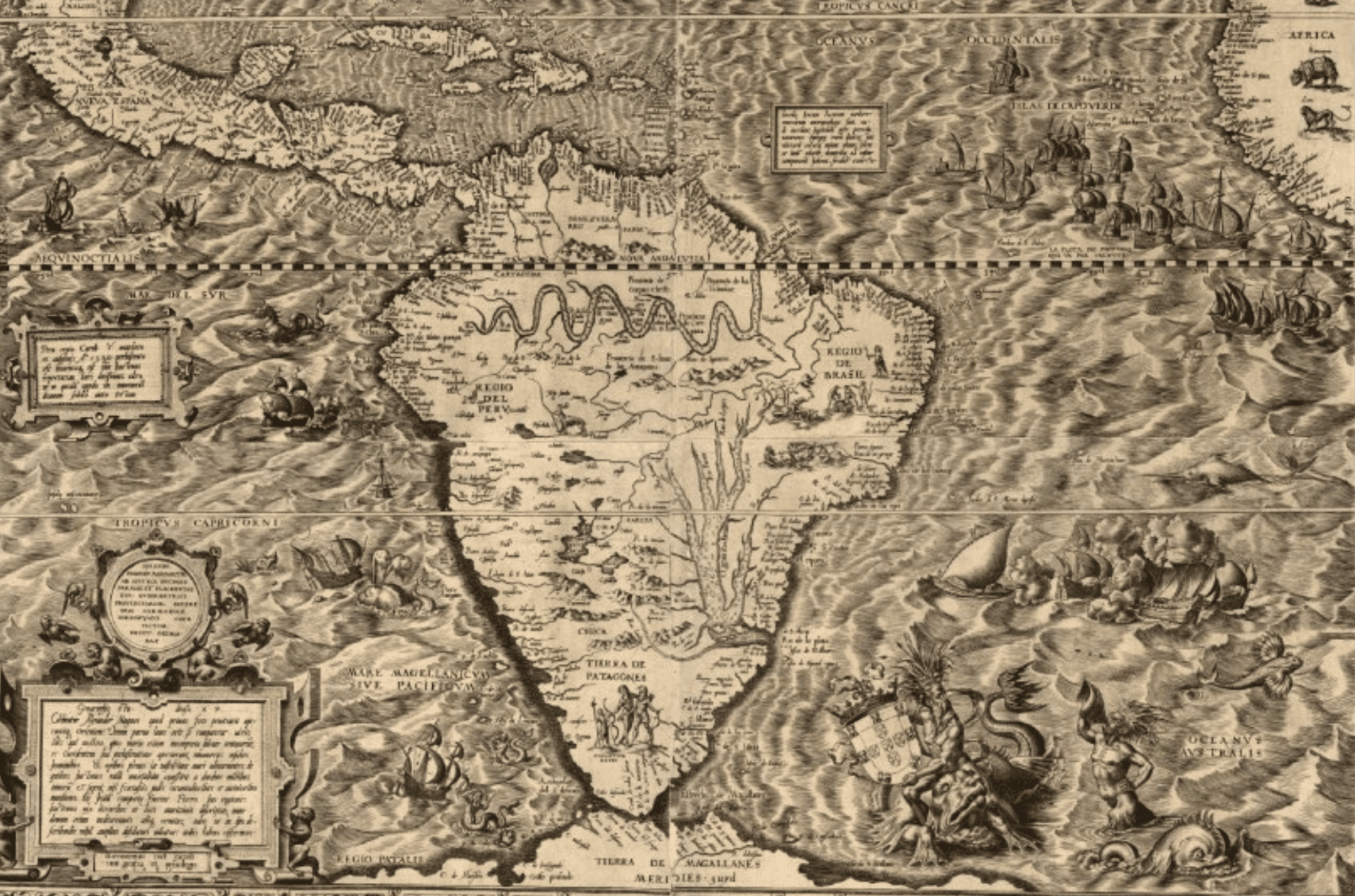

Since the violent imposition of Spanish colonial rule in the 1500s, indigenous peoples in Colombia have been subjected to multiple injuries produced by the extraction of natural resources and external forms of governance. This exhibition, authored and curated by Dr Jennifer Bates, uses visual and textual material including maps, photographs and documents to trace extractivism and the governance of indigenous peoples from the colonial era, to Colombia’s independence after 1819, through to the present day. It examines the continuities in dispossession and subordination of indigenous communities produced by the extraction of gold during colonial rule, and coal extraction since the 1970s. In parallel, the material explores changing forms of governance as they relate to and constitute indigenous rights, and the emergence of indigenous resistance centred on the reclamation of land. While revealing the significant strides made through indigenous political struggles for land, the exhibition also highlights the fundamental, historically rooted tension between indigenous land rights and the logics of extraction that lead to dispossession and damage to their lands.

This map shows a satellite view of the Cerrejón mine in La Guajira department. Covering more than 690 square km, it is the largest open-pit mine in Latin America. The mine has led to the displacement of local populations including indigenous Wayuu, Afro-descendent and farmer communities living in or near to the areas marked for coal extraction. At the time that Cerrejón made its impact assessment, Colombia’s regulatory framework did not require consideration of the impacts on indigenous communities (Gilbert et al 2021). According to Global Legal Action Network’s (GLAN) 2022 complaint against the mine for failure to comply with OECD Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises, the mine uses some 24 million litres of water daily and has diverted more than 17 streams.

Since operations began in the 1970s, the Cerrejón mine has undergone changes in ownership and has been resisted through protests, strikes and numerous legal cases. With the mine’s license set to expire in 2034, NGOs who work with local communities have expressed concern that its closure plan fails to account for its social impacts on communities.

Colombian state company Carbocol and Intercor, a subsidiary of Exxon, sign a 50-50 contract to develop the mine.

The Constitutional Court makes its first ruling in relation to Cerrejón, identifying two areas around the mine as ‘uninhabitable and gravely dangerous to human, plant and animal life.’ Since 1992, there have been more than 17 judicial sentences against the mine.

Carbocol and Intercor sell their shares to an international consortium comprised of Glencore, BHP and Anglo American.

Cerrejón postpones its study into diverting the Rancheria River, the main water source in La Guajira, citing weak carbon prices. The suggested diversion had prompted mass protests from a coalition of indigenous and Afro-descendent leaders, trade unionists, farmers and students.

Glencore becomes the sole owner after purchasing BHP and Anglo American’s shares.

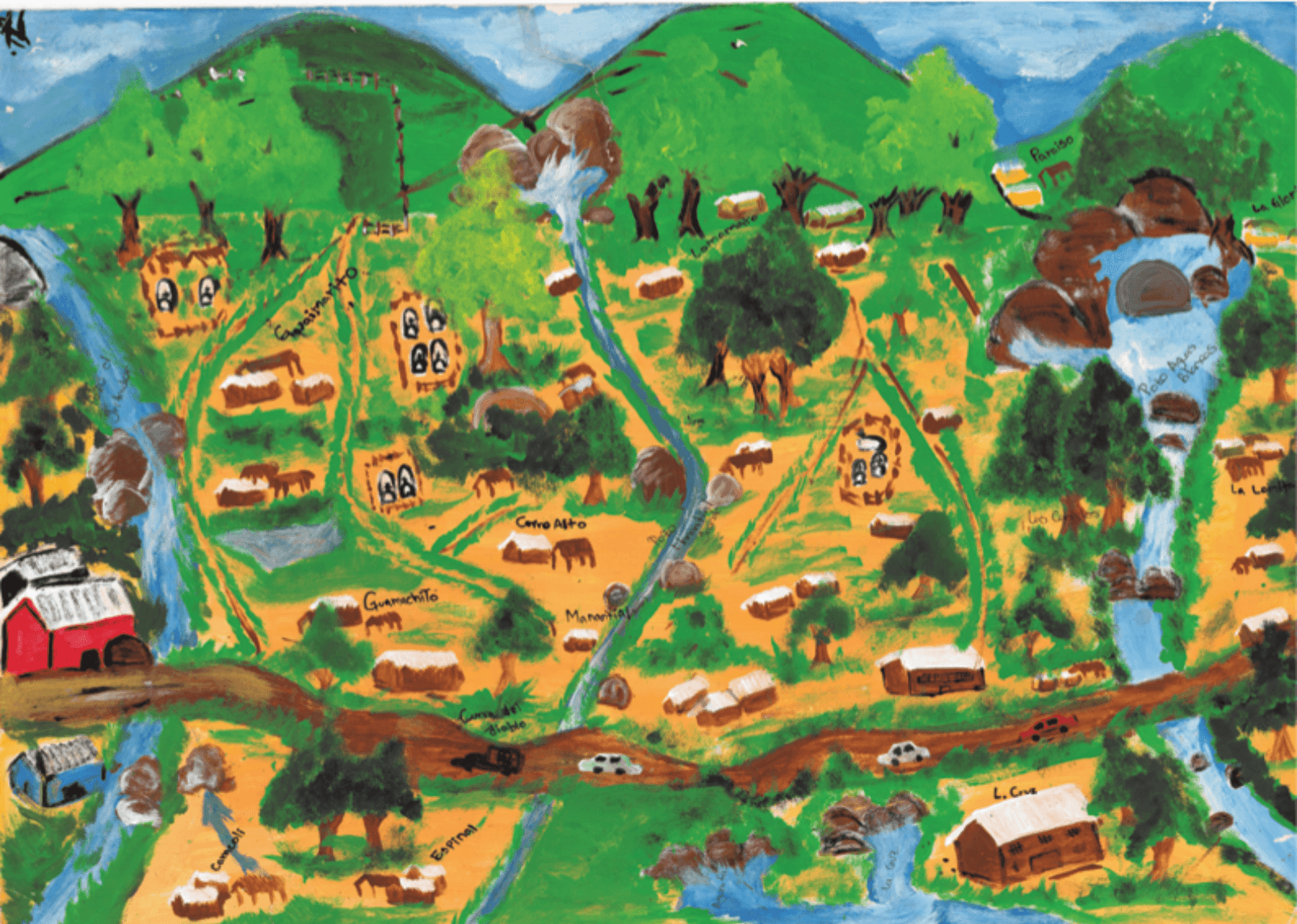

These paintings, produced by Alexander Curvelo from the Wayuu Ipuana clan, show the Lomamato resguardo (reserve) before and after the arrival of the Cerrejón mine. Of the many changes to the resguardo depicted, perhaps the most notable are the loss of water sources and vegetation. The paintings feature in a publication produced by the Colombian NGO Cinep/ PPP titled Agua y mujer. Historias, cuentos y más sobre nosotras, la Pülooi y Kasolü en el Resguardo Wayuu Lomamato (Women and water. Histories, stories and more about us, the Pülooi y Kasolü in the Wayuu reserve Lomamato).

The documentary ‘The Footprints of El Cerrejón: Socio-environmental transformations in the south of La Guajira,’ was released in 2017 and features the testimonies of community members affected by the mine. To see the effects of the mine on the landscape, see 9.57 – 10.12.

In a 2022 report, The UN Special Rapporteur on Human Rights and the Environment David Boyd defined a sacrifice zone as 'a place where residents suffer devastating physical and mental health consequences and human rights violations as a result of living in pollution hotspots and heavily contaminated areas. This report was not the first time that Boyd had intervened in relation to the mine: during the pandemic in 2020, he called on the mine to do more to protect communities from pollution, and to halt operations at one of its sites until it could be proved to be safe.