Constituting Injury

Law, Dispossession and Resistance in South Africa

Resistance: Sophiatown

Sophiatown, as a site of cultural production and resistance, is an icon of twentieth century South Africa. During the 1940s and 1950s, Sophiatown became an emblem of Black urban South Africa, and its production of art, music and literature drew national and international attention. In response to the Group Areas Act, and the subsequent plans for forced removals, a resistance movement was launched with the support of the ANC and other organisations. The resistance was ultimately unsuccessful, but nonetheless influential. This is seen in Jürgen Schadeberg’s iconic photography.

Resistance: Pass Laws

The 1950s was a period of mounting resistance to the racist and oppressive apartheid legislation. This included the Defiance Campaign launched in 1952, coordinated by a multi-party alliance including the ANC and the South African Indian Congress. This national campaign, following the legacy of Mahatma Gandhi’s passive resistance campaigns earlier in the century, consisted of defiance of discriminatory laws included passes, curfews and the segregation of amenities (Worden, 2012). Multi-racial unity and resistance led to the formation of the Congress of the People, members of which signed the Freedom Charter in 1955. This period also saw the formation of the Federation of South African Women (FSAW) (Walker, 1982).

Passes were a central focus of resistance. In 1952, the apartheid regime passed the Natives (Abolition of Passes and Consolidation of Documents) Act. Despite the name, the law consolidated and extended control, though now through documents referred to as “reference books” (Hindson, 1987, p.61). The photograph here was captured by a photographer for Drum magazine during a mass demonstration outside of Johannesburg City Hall in 1957. The image is a powerful statement of the historical continuity of pass laws and oppression.

Wathint’ abafazi, Strijdom! Wathint’ imbokodo uzo kufa!

Now You Have Touched the Women, Strijdom! You Have Struck A Rock, You Will Be Crushed.

In 1952 the apartheid regime announced its intention to make passes, now called reference books, mandatory for Black African women as part of urban influx control (Posel, 1991; Schmidt, 1983). This spurred on widespread resistance which brought women of all population groups together. On 27 October 1955, with leadership from FSAW, 2,000 women gathered at the Union Building in Pretoria in protest of apartheid laws. The following year, on 9 August 1956, 20,000 women gathered. The women, led by Lilian Ngoyi, Sophia Williams de Bruyn, Rahima Moosa, and Helen Joseph, delivered their demands to Prime Minister Strijdom. The chant “Wathint’ abafazi, Strijdom! Wathint’ imbokodo uzo kufa! (“Now you have touched the women, Strijdom! You have struck a rock, you will be crushed”) was used during the gathering. In the following years, women’s resistance movements occurred across the country (Schmidt, 1983, Walker, 1982).

Despite the strong resistance, by 1963 it was mandatory for all Black African women to carry a reference book (Posel, 1991; Schmidt, 1983).

https://www.jurgenschadeberg.com/

Resistance and Repression

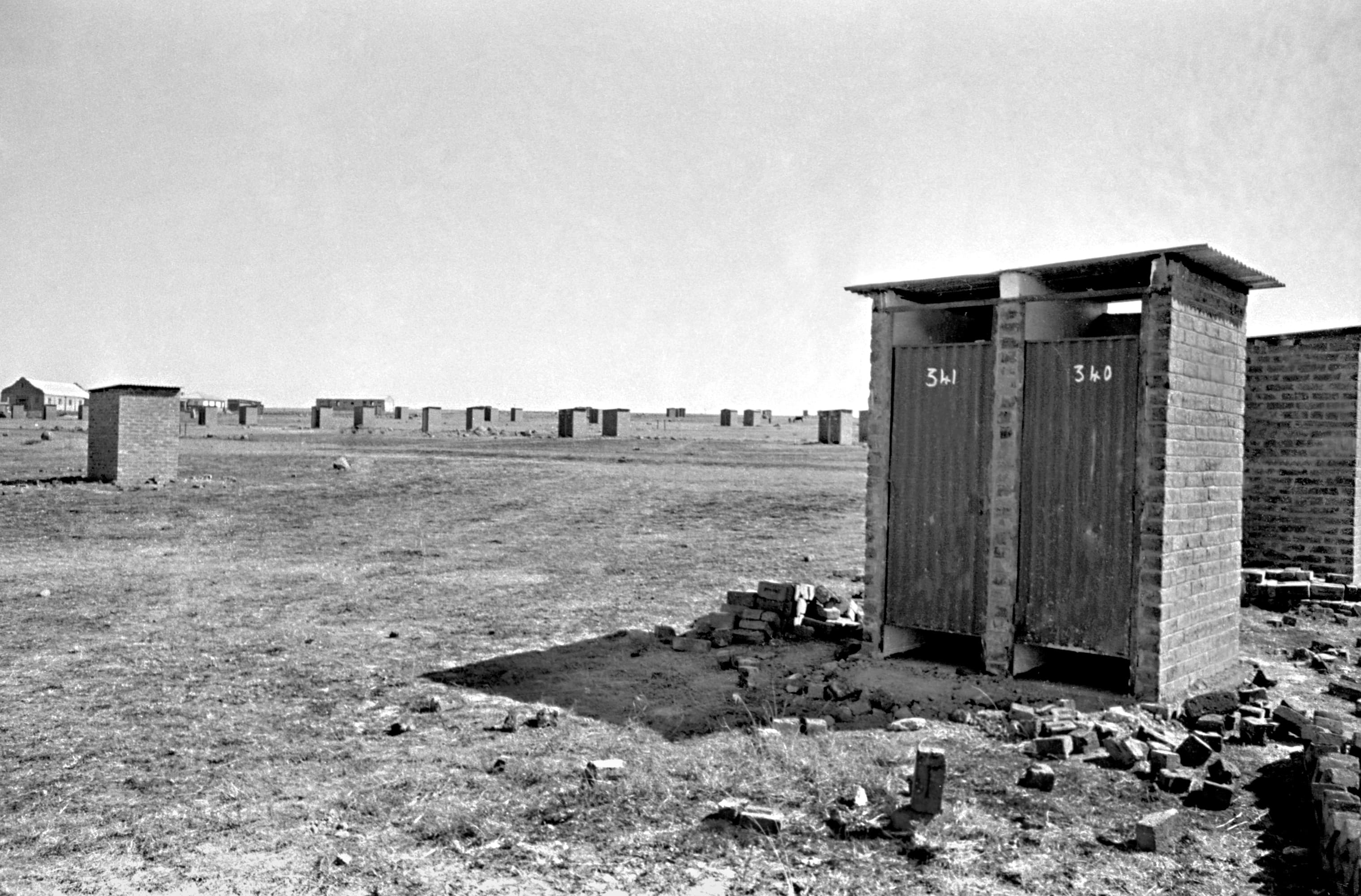

Resistance to pass laws continued, and by 1960 famously led to the burning of passes. This image was taken in a township on 3 March 1960.

On 21 March 1960, an anti-pass demonstration took place in Sharpeville, in Transvaal province. Apartheid security forces opened fire, killing 69 people and injuring hundreds.

The Sharpeville massacre was a turning point in South African history. In the aftermath, the apartheid regime banned political organisations and extended its militarised control of the Black population of South Africa. Laws continued to be utilised to control and dispossess, including the pass laws (Savage, 1986). Resistance continued, underground and abroad.

Pass burning in the townships, 1960. Photographer unknown.

The ‘New’ South Africa

Following decades of apartheid oppression, and centuries of colonialism, South Africa transitioned into a democracy in 1994. This ‘new’ South Africa was consolidated by the 1996 Constitution, which included a substantial Bill of Rights. The 27 fundamental rights enshrined in the Constitution are represented in a series of fine art prints entitled the Images of Human Rights print portfolio, housed at the Constitutional Court of South Africa.

In this artwork by Samkelo Bunu, Land and Property Rights are represented. Through the classical pillars, Bunu references the responsibility of parliament in relation to land and housing rights. The destruction of the house by one of these pillars is suggestive of the injuries caused by historical governments. The papers throughout the image poignantly indicate the reach and power of the law. See here.

With ongoing poverty, inequality, and landlessness, the debate continues as to whether the transition of the 1990s has led to a ‘new’ South Africa.