King's College London

Nigeria: Practices of Colonial Power in the Niger Delta

Authored and curated by Naluwembe Binaisa

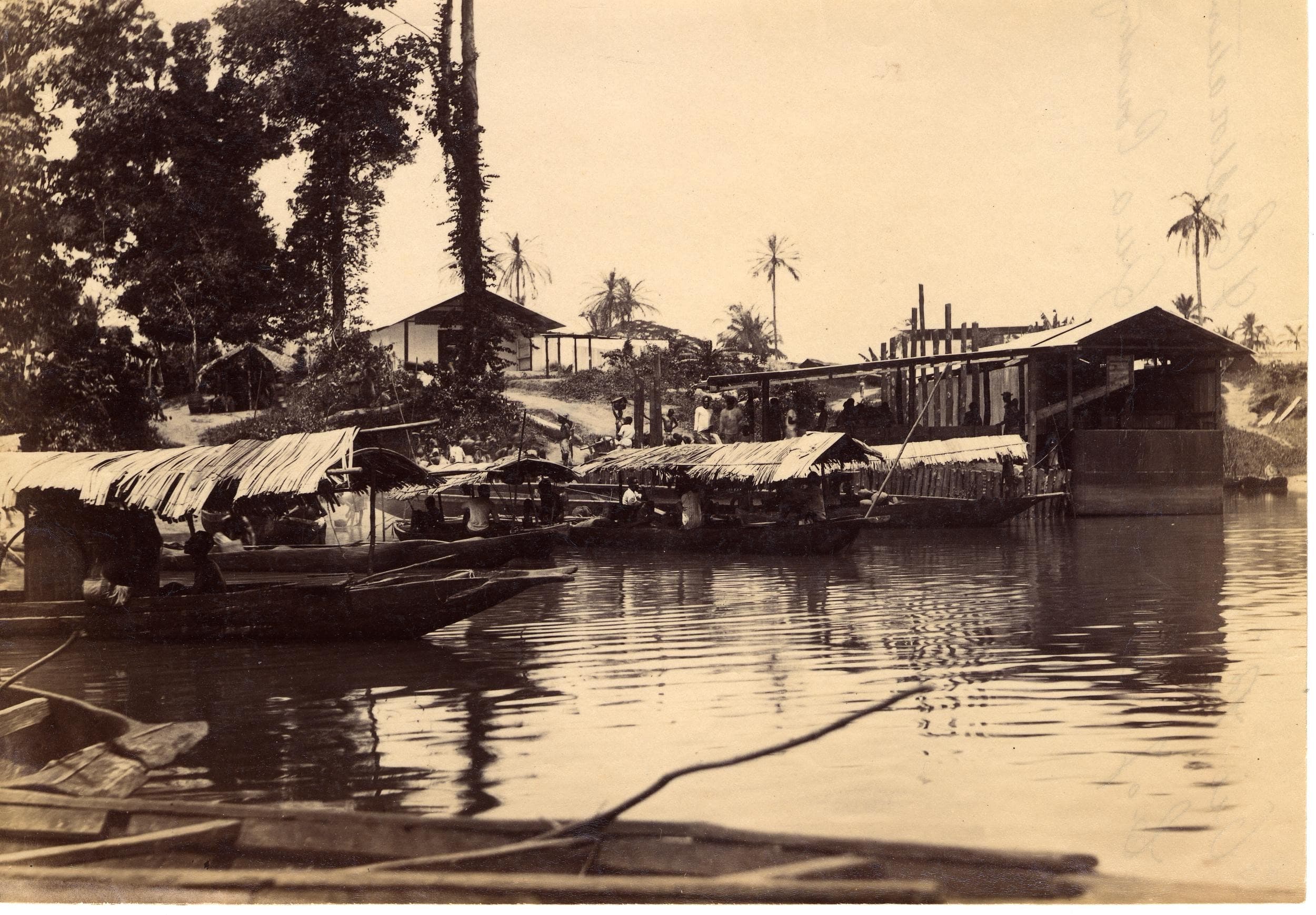

Time echoes through this preliminary visual enquiry into practices of colonial power in the Niger Delta. It seeks to trace the complex iterations of injury as well as the multi-sited cycles of agency. The people, land and environment on this rim of the West African coastline, whose interior is bisected by the mighty River Niger, have for centuries been imbricated in the violent dynamics of the Africa <> Europe compact. From slavery to palm oil, to petroleum and poverty, these people, their land and environment persist despite centuries of hope dressed up as civilizing missions, dispossession framed as material progress. At the center of these seemingly endless iterations of violence, hope, conflict and resource extraction, are the exigencies of . This forms the bedrock on which practices of colonial power rest to sustain multi-dimensional injury, which continues to bleed into postcolonial Nigeria. Fieldwork and ongoing research across the course of this project will seek to enrich this enquiry and incorporate private and alternative archives, documents, images, objects and testimonies, to further interrogate colonial practices and their afterlives. In this exhibition four interrelated themes trace these sedimented flows: Treaties and Maps; Symbolic Power; Circuits of Extraction and Production; Agency and Resistance.

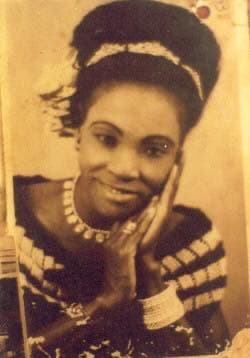

Women, Rights and Resistance

Women were at the forefront of resistance and agency throughout the colonial period. They led struggles for rights, justice and political representation that cut across class and ethnicity lines as they mobilised women. Chief Margaret Ekpo shown in this image, born in Creek Town 1914 was a formidable and ground-breaking politician who mobilised against the injustices of British colonial rule in the Eastern region which included the Niger Delta region (Ukpokolo 2020). Margaret Ekpo joined the Nigerian Women’s Union which Funmilayo Ransome-Kuti founded in 1949. Theirs was a vision which saw the liberation of Nigeria as directly linked to women’s upliftment and advancement in all areas of their life (Johnson-Odim and Mba 1997). The Enugu Colliery massacre of 1949 against striking miners was another point of their mobilization. Ekpo was the first woman appointed as a Chief to sit in the Eastern House of Chiefs in 1954 and was elected in 1961 to represent Aba North Constituency in the Eastern Regional House of Assembly (Ukpokolo 2020).

The Women’s War in 1929, also known as Ogu Umunwanyi, was a turning point in political activism and mobilisation across Nigeria. In Nigeria today women continue to fight and mobilise under the banner of unity and upliftment for all women. Important initiatives include #WOMANIFESTO: WHAT NIGERIAN WOMEN WANT - WARDC (wardcnigeria.org) and the Global Feminisms Project (umich.edu). A discussion of the Women’s War 1929 that draws on the British colonial government’s Aba Commission of Enquiry documents can be found on this link Ogu Umunwanyi, Ekong Iban, Women’s War: A story of protest by Nigerian women - The National Archives blog.

Administrative Power and Resistance

Ikot Abasi in present day Rivers State is a site where intersecting layers of administrative power and resistance can be traced. Amalgamation House, in this photograph, is the former home and office of Lord Lugard. It is also where the 1914 Treaty of Amalgamation that joined Southern and Northern Nigeria and the Colony of Lagos into one country Nigeria, was signed. Contemporary media coverage focuses on the dilapidated state of the site and squandered tourism opportunity (Uyo 2021).

The use of social media has seen a growth in what can be regarded as contemporary interest in the colonial legacy, giving access to diverse audiences. The blog post on Ikot Abasi by the artist and writer Enefaa is one such example where the visitor is introduced to this problematic heritage (2018). The virtual and physical visitor to Ikot Abasi encounters centuries old injury, layered through one site as well as the courage and resistance of the population.

On this same site where those who held the instruments of colonial governance sat, the unspeakable violence of slavery remained etched in the landscape. The slave trade ‘bridge of no return’ with underground holds to torture ‘stubborn’ slaves survives on this site, as does the Women’s War commemoration stone for those women massacred by colonial government forces on 15th December 1929. The ‘whitewash’ enquiry held in Aba erased Ikot Abasi’s bloody pivotal role in the Women’s War. Their resourceful unity, collaboration and organization cutting across ethnicity and class, instead minimized, demonized and ghettoized.

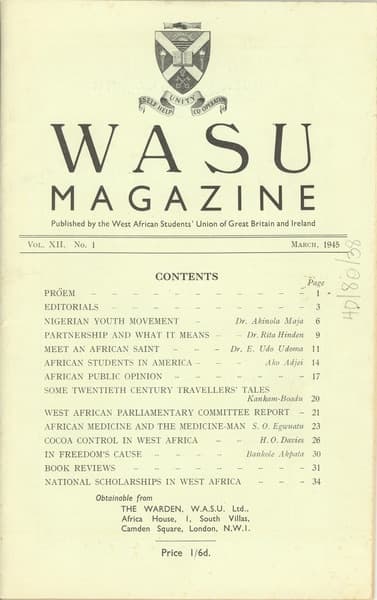

Transnational Agency and Resistance

The struggle for rights and for the freedom of Africans was transnational in reach particularly through the efforts of those students who gained access to education abroad during the colonial era. The West African Students Union (WASU) founded in 1925 brought together members studying in a range of institutions across Britain. The image on the left is of the 1945 edition of the WASU Magazine held in the W.E.B. Du Bois Papers. The magazine gave voice to West African student mobilisation against colonialism and fostered radical Pan-African resistance (Adi 1993). WASU members were at the forefront of mobilising across the continent as well as in Britain and the USA against the situation in Nigeria, an example being the proposed Nigeria Constitution in 1945 (Nzemeke 1991). WASU members such as Kwame Nkrumah went on to become future political leaders of newly independent states.

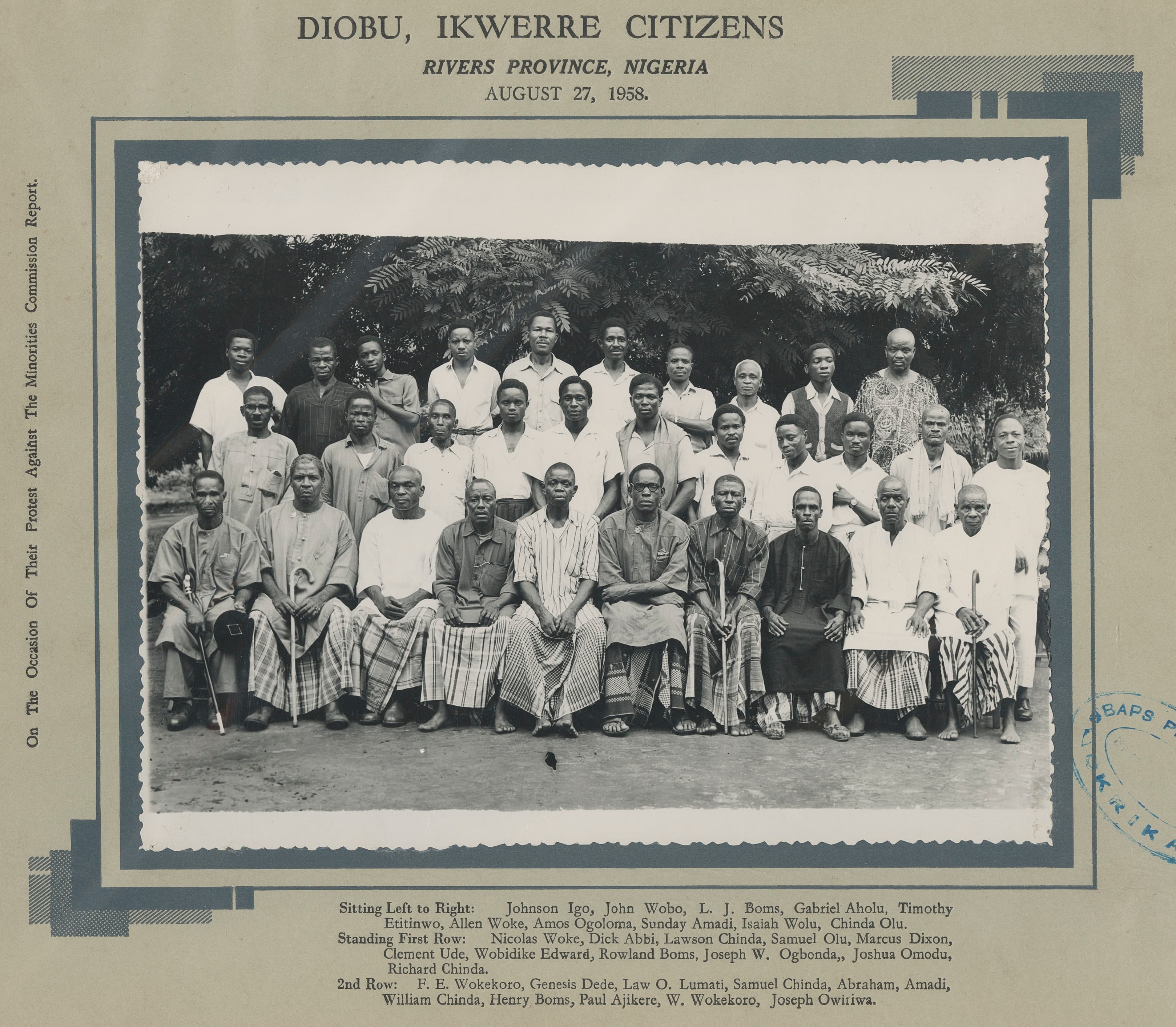

Representing Protest: Minorities Concerns

In the run up to Independence for Nigeria, representation and protection were core issues raised by Niger Delta communities and other ethnicities across the country who considered themselves minorities. The Minorities Commission was set up by the colonial government in 1957 in response to the fears and demands of minorities in Nigeria. Many advocated for the creation of new states as part of the Independence settlement that was under negotiation (Akinyele 1996). The report ultimately found against new state creation as a solution for minorities fears.

This group portrait taken in Diobu, Ikwerre of the communities’ prominent citizens, two years before independence, was in protest at the publication of the Minorities Commission Report, and its rejection of the proposal to create a state to protect the interests of Niger Delta minorities. This Report is often known as the Willink Report, named after its chairman Sir Henry Willink. The names of all those featured in the group portrait are inscribed beneath the image, and the frame is also inscribed with the date and its purpose.

Hope and Futurity

Hope accompanied headlines such as this one in the Eastern Nigeria Guardian newspaper trumpeting an oil strike in Ogoniland. Hope that was to descend, through complex drivers, into the violence of oil-related conflict (Obi 2009). In this image a young person works the printing press while his editor looks on supervising his training for a better future on the eve of Nigeria’s independence. According to documentation on the back of the photograph at the National Archives: ‘Dr. Azikiwe, Prime Minister of the Eastern Region founded a number of daily papers in attempt to spread an all African press throughout Nigeria. The Guardian is one of this group which also includes the Nigerian Spokesman, Onitsha; the Southern Nigerian Defender, Ibadan; the Eastern Sentinel, Enugu and the Daily Comet, Kano.’

Art Challenges History

Art challenges history and the future yet to come in Wilfred Ukpong’s BC1: Niger-Delta / Future-Cosmos activating Indigenous cosmologies to chart a way forward and mitigate injury. In this image entitled - BC1-ND-FC: Strongly, We Believe in the Power of this Motile Thing That Will Take Us There #2 -- four young figurately oil drenched survivors, reach out towards the futurity of hope. They ride the waves of change leading the way, despite living with intense oil blight and environmental devastation (Karmakar 2023). Ukpong’s work informed through a committed participatory social practice, makes visible a counter-archive that draws on community’s enduring ways of seeing and being in the world. It seeks to upturn the harmful order of things such as separation from the environment. An order entrenched through the naturalization of harmful colonial practices of power. In Ukpong’s work the complex entanglement of aspirations, betrayal, hope and spirituality come to the fore. Ancestors speak through the land and digital technology, charting a way to potential futures.

FUTURE - WORLD - EXV (2019)

Film by the artist © Wilfred Ukpong