King's College London

Nigeria: Practices of Colonial Power in the Niger Delta

Authored and curated by Naluwembe Binaisa

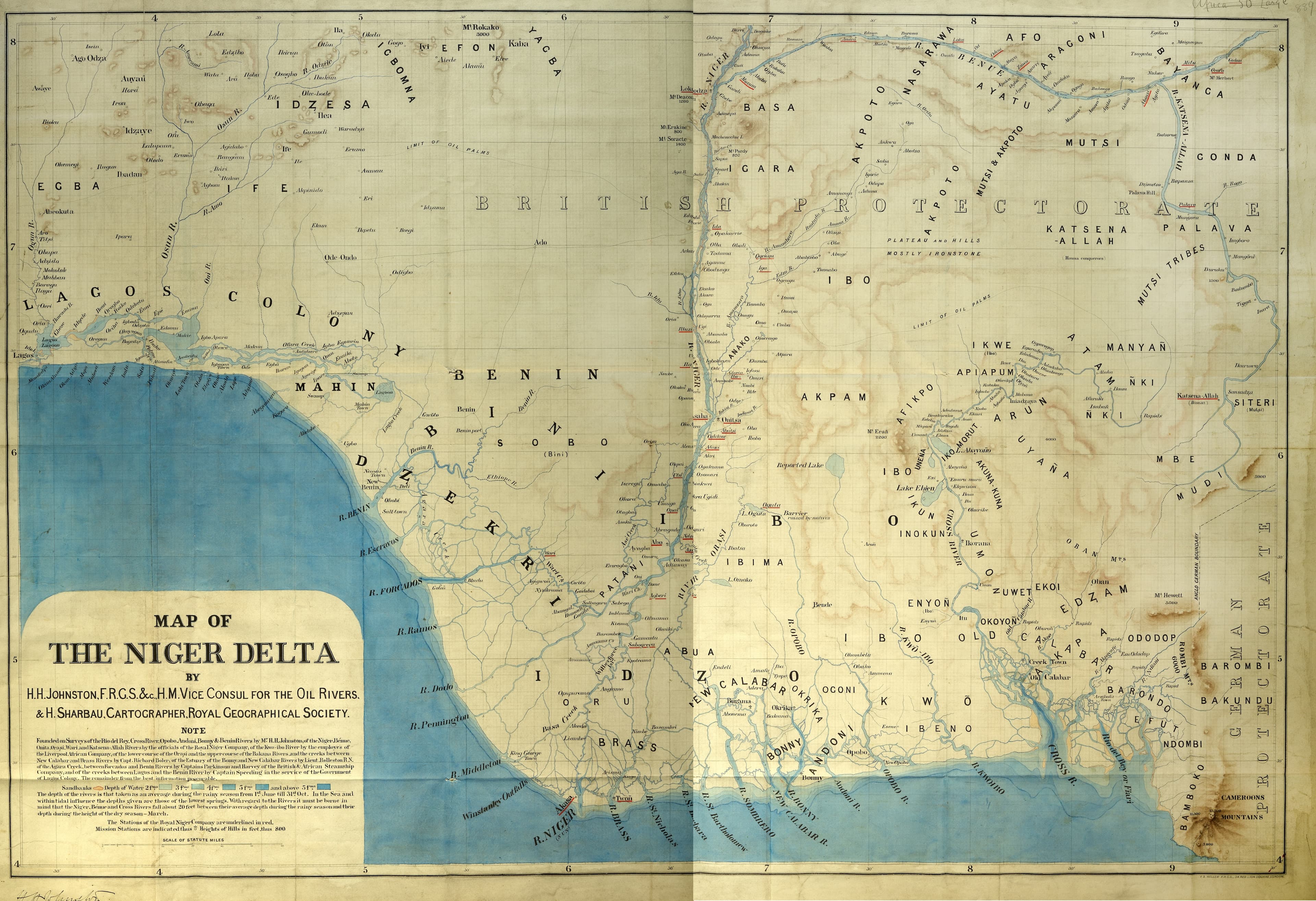

Time echoes through this preliminary visual enquiry into practices of colonial power in the Niger Delta. It seeks to trace the complex iterations of injury as well as the multi-sited cycles of agency. The people, land and environment on this rim of the West African coastline, whose interior is bisected by the mighty River Niger, have for centuries been imbricated in the violent dynamics of the Africa <> Europe compact. From slavery to palm oil, to petroleum and poverty, these people, their land and environment persist despite centuries of hope dressed up as civilizing missions, dispossession framed as material progress. At the center of these seemingly endless iterations of violence, hope, conflict and resource extraction, are the exigencies of . This forms the bedrock on which practices of colonial power rest to sustain multi-dimensional injury, which continues to bleed into postcolonial Nigeria. Fieldwork and ongoing research across the course of this project will seek to enrich this enquiry and incorporate private and alternative archives, documents, images, objects and testimonies, to further interrogate colonial practices and their afterlives. In this exhibition four interrelated themes trace these sedimented flows: Treaties and Maps; Symbolic Power; Circuits of Extraction and Production; Agency and Resistance.

Assemblages of Power

Infrastructures of Dispossession

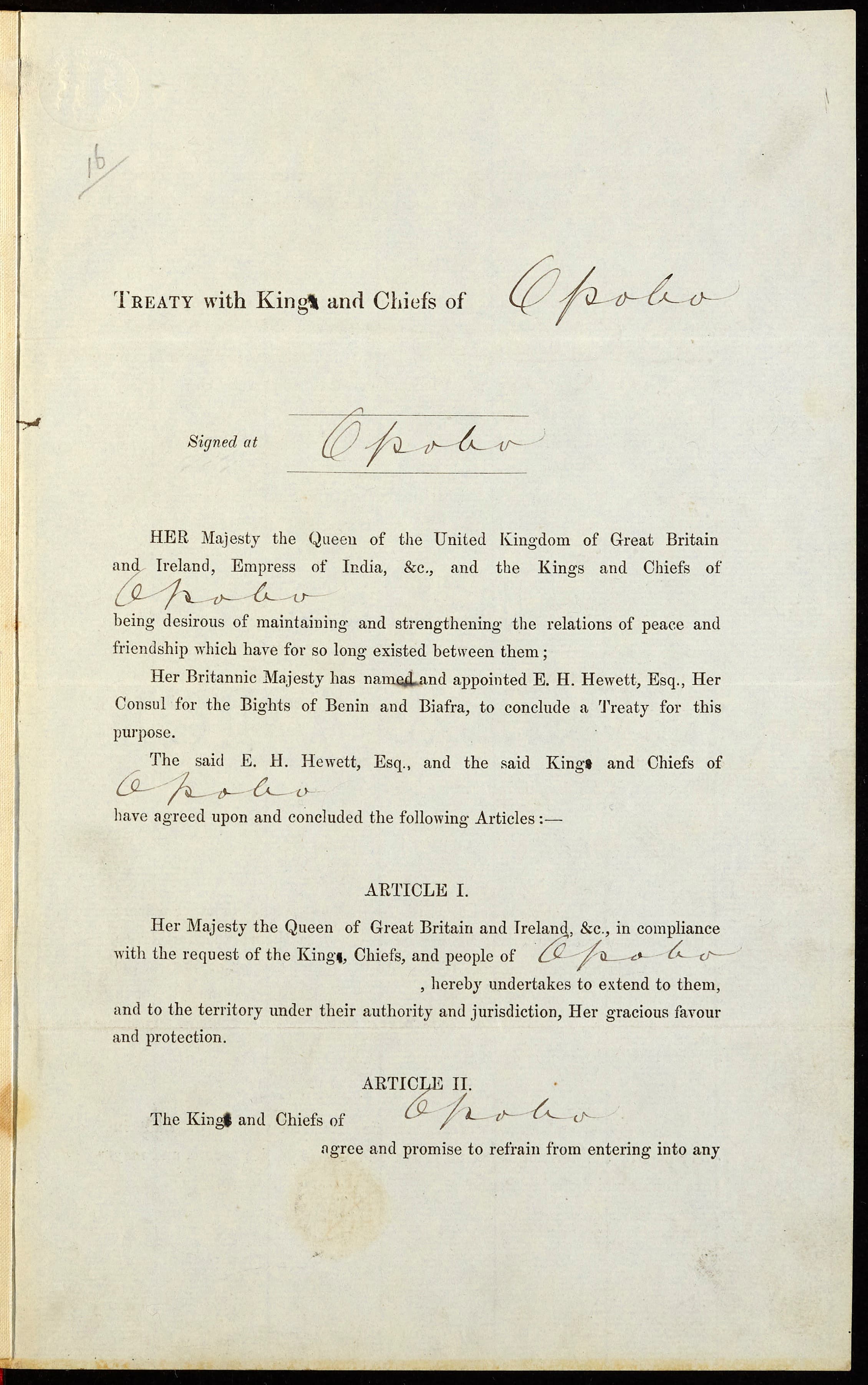

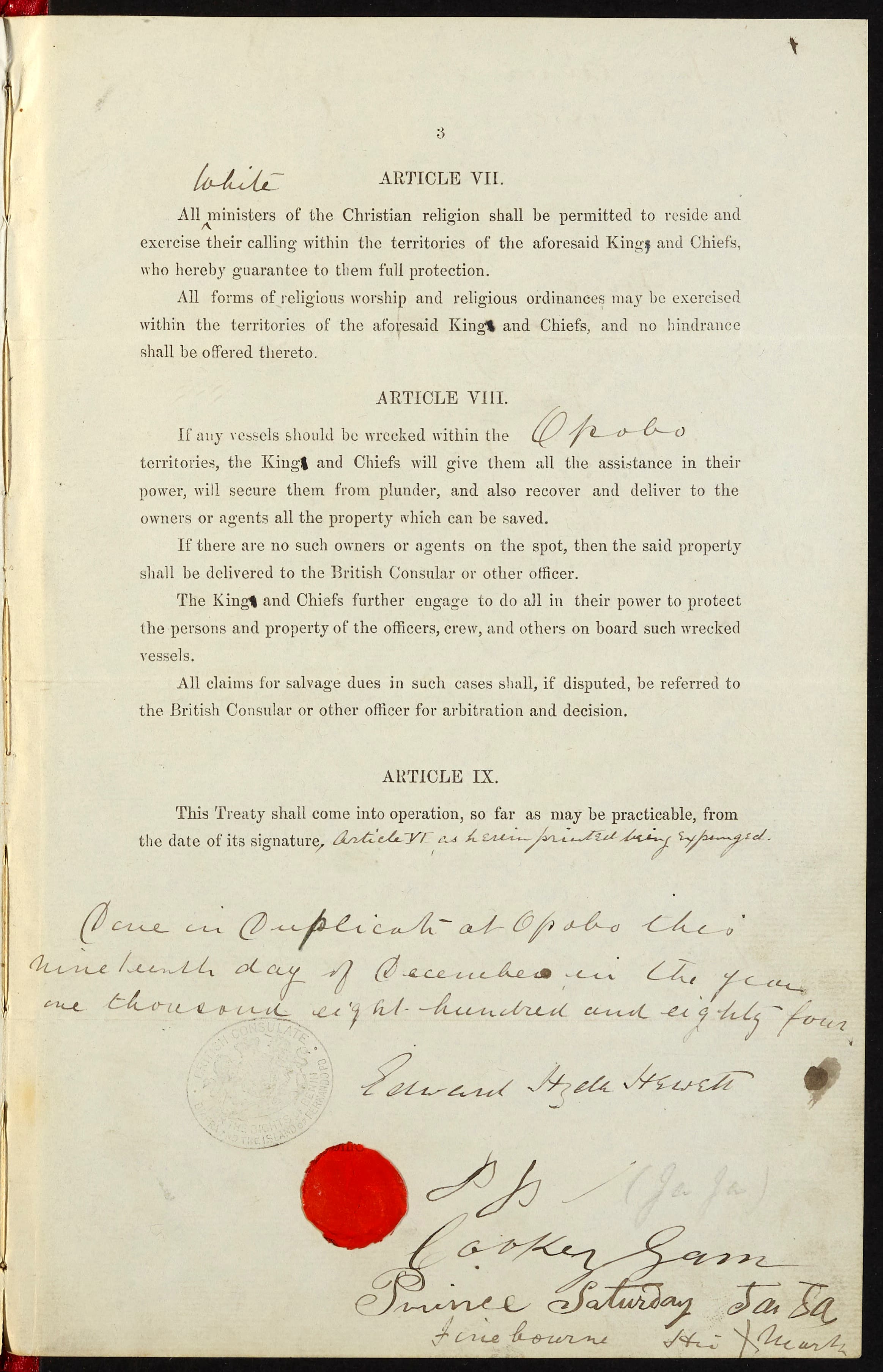

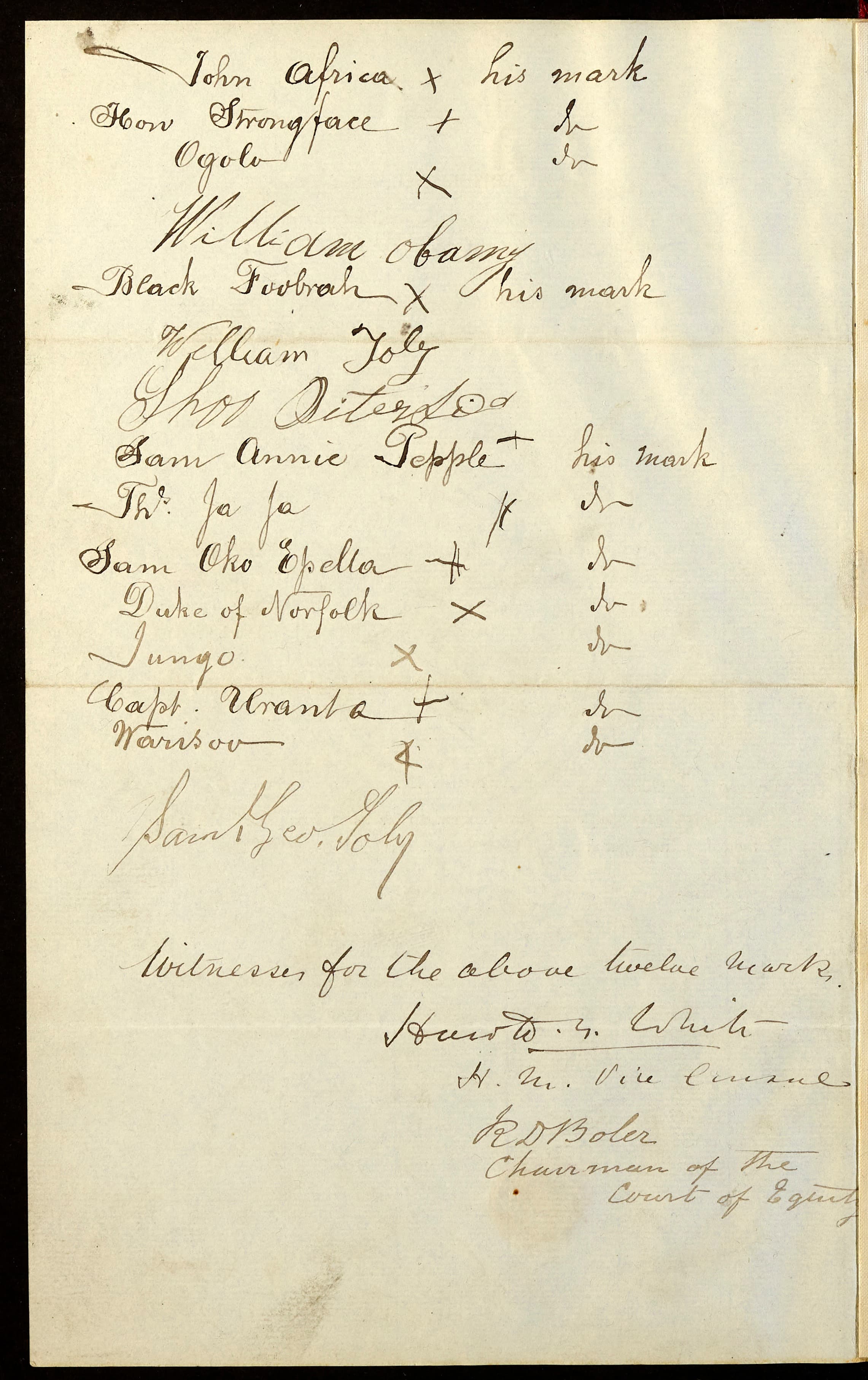

Treaties that were termed treaties of ‘protection’ legitimized the juridical authority of Empire (Dike 1956). The Opobo Treaty follows the template laid down in previous treaties signed between Britain and various kings, queens and chiefs of the Niger Delta. These Treaties reflected the intensified competition between Britain and other European states in the run-up to the infamous 1884-1885 Berlin Conference. Where they had the temerity to divide Africa amongst themselves, not once alluding to the violent wars, massacres and subjugation that were background to their powerful position (Falola 2009). Their self-ascription of ‘original ownership’ continues to mark the postcolonial state through the normalisation of such differentiation markers as anglophone and francophone Africa.

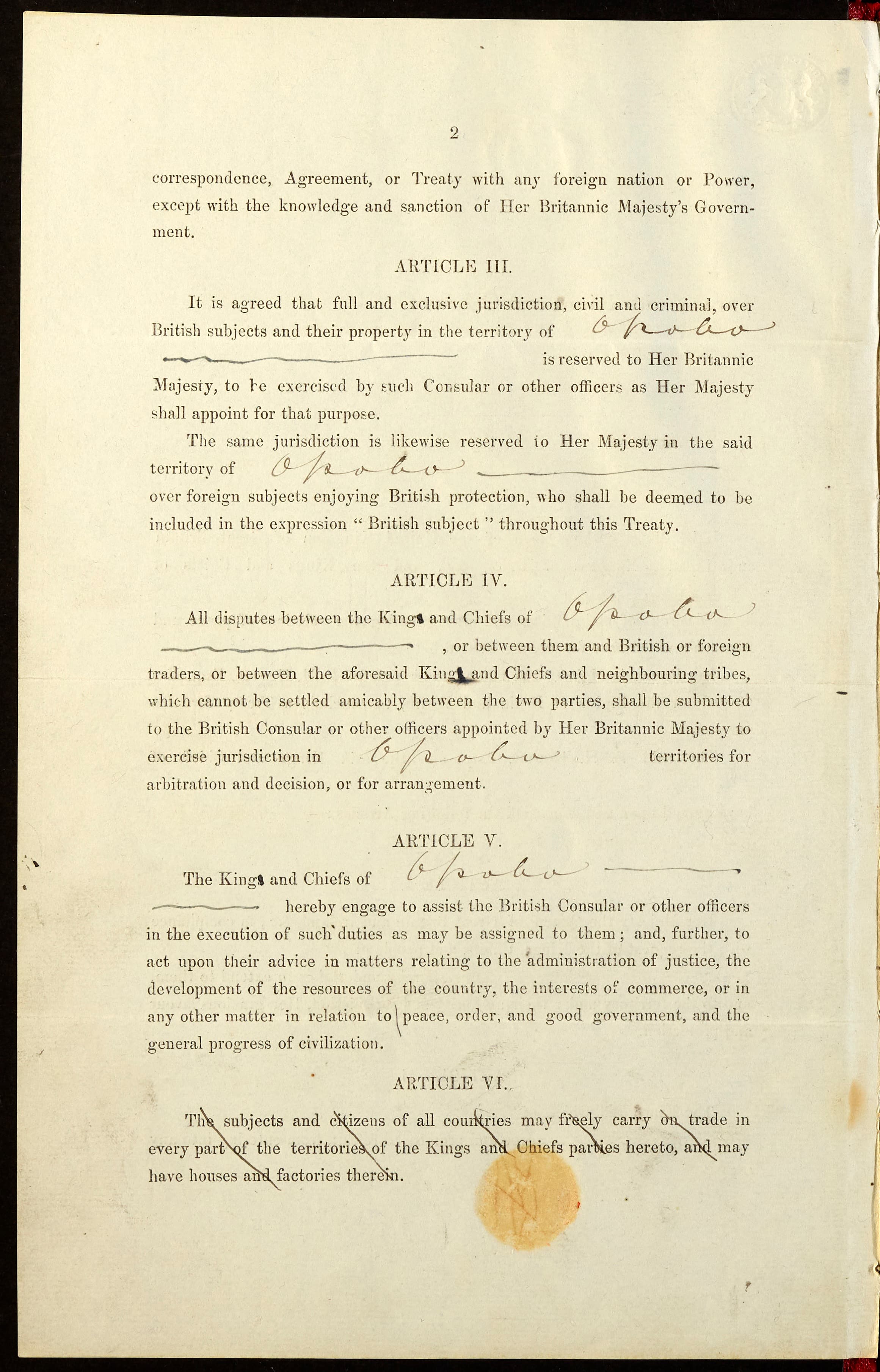

Treaties formed the foundation for governance of the resource extraction economy and echo in disputations against contemporary land use acts (Ebeku 2002). To colonisers treaties and maps were key tools for asserting dominion, legitimizing and enacting dispossession. Article I of the Treaty granted Protection as requested by said nation, king, queen and/or chiefs. Article III and Article IV consolidated Britain’s juridical authority to assign, legislate and adjudicate over territory and commerce. Article V burdened African signatories to assist the colonisers in their every request.

Whilst in Article VII a racial distinction is inserted to specify that rights granted to Christian ministers are only applicable to those who are ‘white’. Despite the strategic contribution of Black colonial missionaries to the political goals of Empire, this appears to be a targeted distinction. It follows in the wake of the successful missionary activity of Samuel Ajayi Crowther the first Black African Bishop of West Africa, consecrated twenty years prior in 1864, and the other Black ministers who followed.

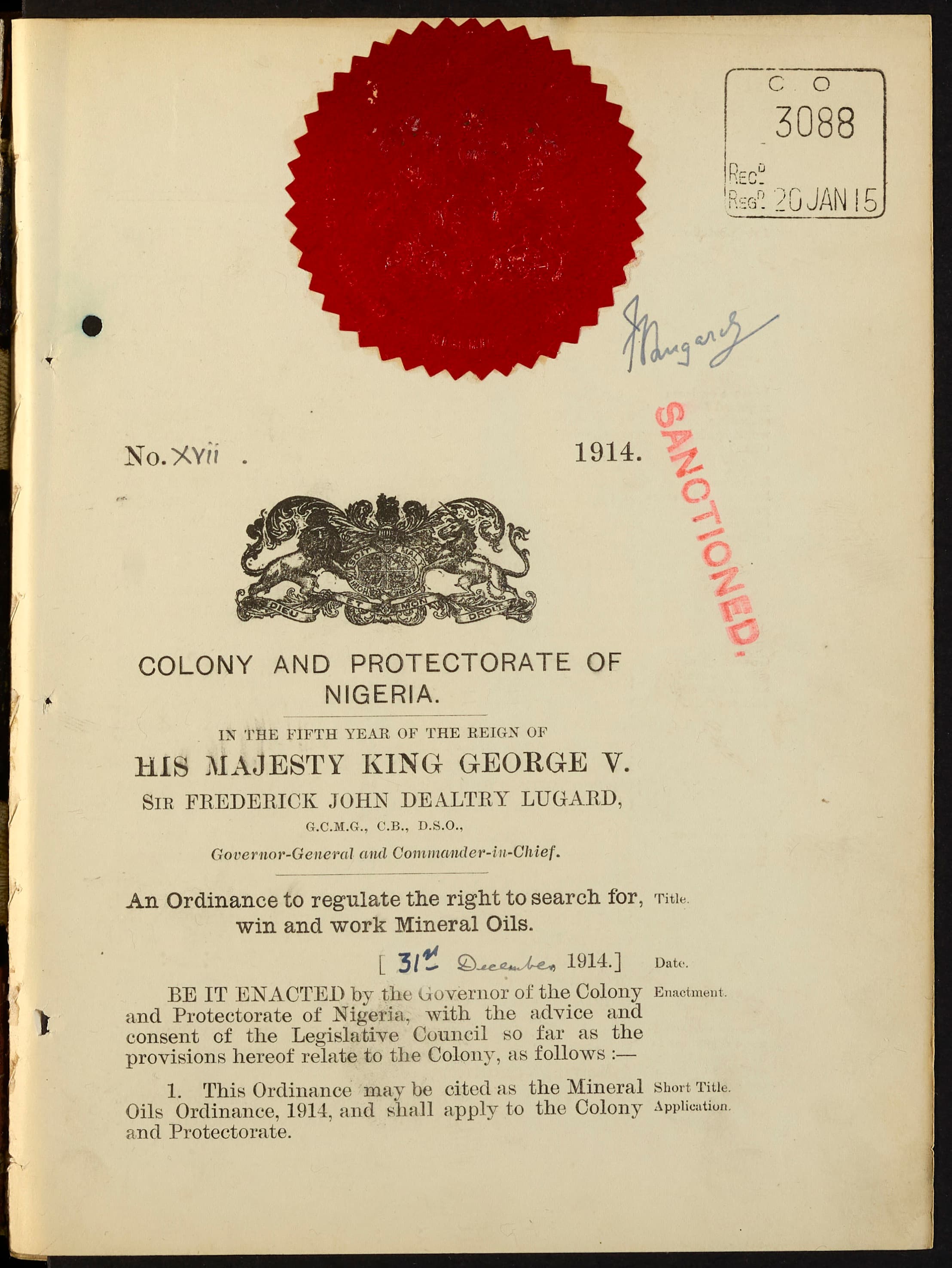

Mineral Oils Ordinance 1914

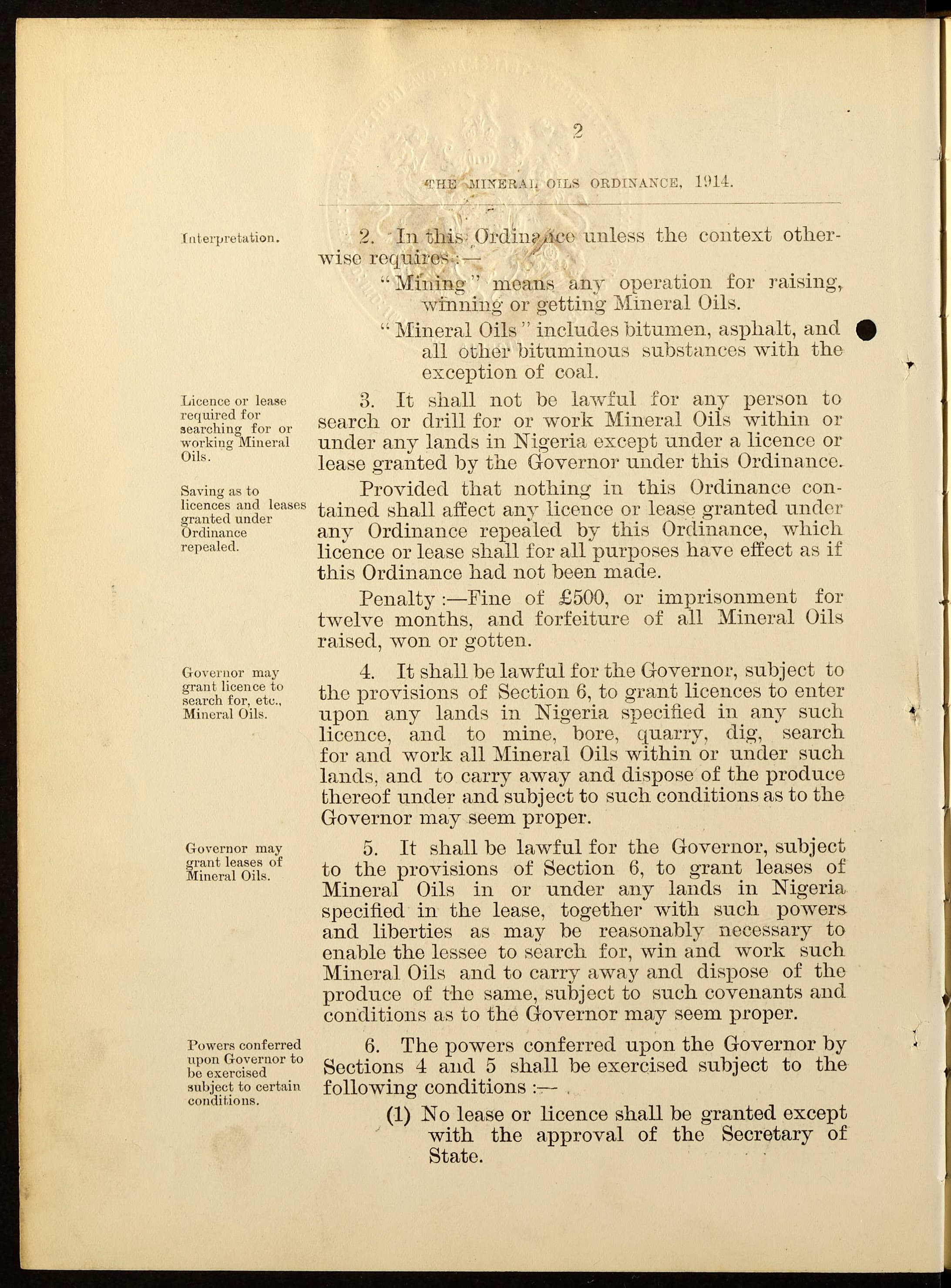

There was contradiction and tension between a coercive and imposed colonial juridical system that claimed to prioritise social justice through advancing freedom, initially to trade (Ibhawoh 2002). Nevertheless, as Ibhawoh notes: ‘Law was an effective instrument both for fostering colonial hegemony and for guaranteeing the maintenance of social order on a scale conducive to colonial interests’ (2002:55). The Mineral Oils Ordinance signed at the end of 1914 invested sweeping powers of authority to the Governor General as lead representative of the British government and Crown. These Ordinance are regarded as instituting the first generation of oil governance regimes, providing a pathway to foreign firms to acquire licences from the Crown for oil exploration. By 1938 Shell d’Arcy gained massively from this legislation when it was granted a monopoly, this was later diluted after WWII at the insistence of the USA, and Mobil (1955), Tenneco (1960), Gulf Oil (1961), Chevron (1961), Agip (1962) and Elf (1962) joined in quick succession (Ukiwo 2018).

The colonial government had oversight across all operations regarding mineral oils as noted in the ‘Interpretation’ section of the Ordinance. Draconian rights invested in the Governor General included those stipulated in point number 3 to 6 in the ‘Licences and Leases’ sections. Point number 4 is of note as it gave the Governor General comprehensive rights and powers over all land above and below ground, in the pursuance of the extraction of mineral oils. Subsequent sections of the Ordinance granted the Governor General the right to impose a range of sanctions on those who did not adhere with the regulations of the Ordinance. Whilst point number 9 granted the Governor the right to enact any additional legislation he deemed necessary to fulfil the Ordinance. This juridical approach and logic were the genesis of similar far-reaching powers over land rights and mineral oils extraction after Independence, which were retained and extended by subsequent post-independence governments (Ebeku 2002).